Last week, the History Council of NSW held our flapship event, History Week 2016. One of the History Council’s members, the Jessie Street National Women’s Library, hosted a week-long exhibition exploring the diversity of women’s experience as neighbours. The library made use of their rich collection to illustrate women’s experiences that ranged from simple over-the-fence support for one another, to working on a national and international scale for the welfare of other women. The History Council of NSW is delighted to share some of the stories unearthed in the Library’s exhibition.

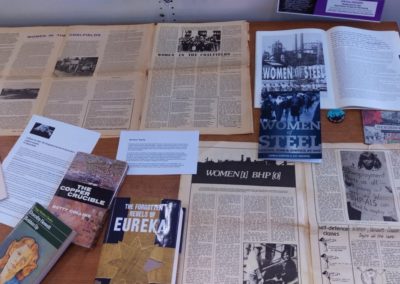

Day One: Showcased on the first day of Library’s History Week exhibition was women’s involvement in the fight for workers’ rights. One of the many ways women have acted as neighbours were in fighting for their own rights and the rights of others. Politically active women have long fought for workers’ rights, but the dominant historic narrative has often diminished their participation. Whether as organisers, workers or the wives of workers, women have long been involved in political action in Australian industry and through political associations with communism and the socialist movement.

Through the library’s collection, it is possible to rediscover radical activism such as Jean Devanny’s Sugar Heaven, a novel documenting sugar cane worker strikes in Queensland in the 1930s, or the long history women had as auxiliaries in the coalfields, published as oral histories in the newspaper Mabel. These women organised their communities and coordinated efforts amongst local families. Conflict between nationalist and class loyalties exposed the tensions rife in concepts of neighbour and comrade.

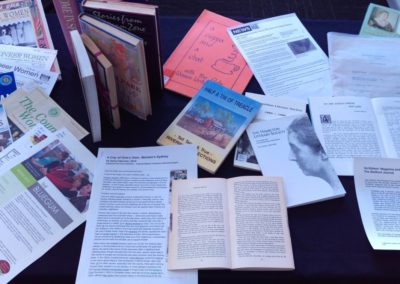

Day Two: On Tuesday 6 September the exhibition explored rural women in the Library’s collection. The serials collection of the Library is a trove of stories depicting a sense of community ownership of local issues by rural women across Australia.

The Country Women’s Association (CWA) was formed in 1922 in response to a lack of health services and a sense of isolation amongst rural women. The members established baby health care centres, funded bush nurses, built and staffed maternity wards, hospitals, schools, rest homes and even holiday cottages. They have been initiators, fighters and lobbyists who have provided social activities as well as educational, recreational and medical facilities.

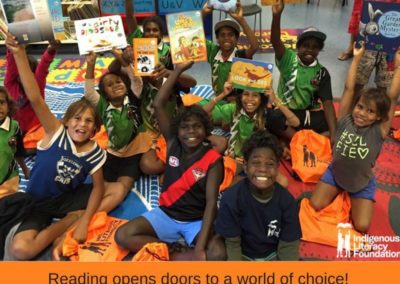

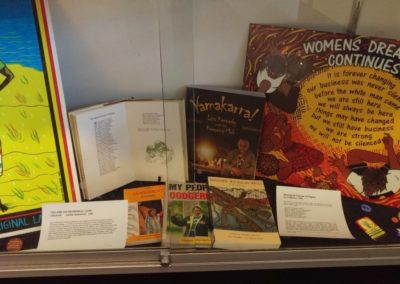

Day Three: The staff at Jessie Street celebrated the day by marking Indigenous Literacy Day.

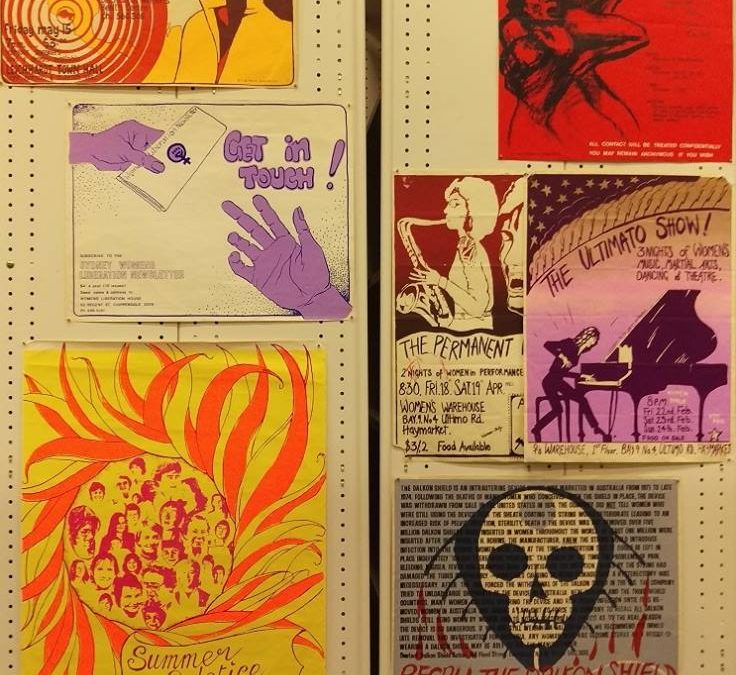

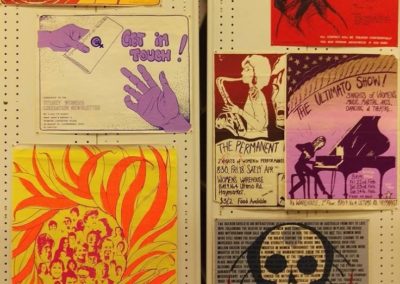

Day Four: On Thursday 8, the Library exhibited some of the posters in their collection designed by the Women’s Warehouse Screenprinters.

This collective operated in The Women’s Warehouse (1979–1981) which was located in Haymarket, just down the road from the Library, and provided an unofficial headquarters for the social and cultural activity of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Sydney. The Women’s Warehouse Screenprinters was one of the most significant collectives to operate in the space. The Library exhibition included a display of a number of the books to which she refers together with Ruth Park’s great description of a neighbourhood New Year’s Eve in Surry Hills in ‘The Harp in the South’ (1948).

Day Five: On the last day of the exhibition, the Library showcased some of its books and posters which highlight Indigenous issues. The ‘Aboriginal Charter of Rights’, written by one of the great Aboriginal authors and poets, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, in 1962, is a powerful and emotional plea for justice.

“You devout Salvation-sellers

Make us neighbours, not fringe-dwellers,

Make us mates, not poor relations,

Citizens, not serfs on stations.

Must we native Old Australians

In our land rank as aliens?

Banish bans and conquer caste,

Then we’ll win our own at last.”

The poem was presented to the 5th Annual General Meeting of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, held in Adelaide in 1962. It was published in the 1970 anthology, ‘My People, A Kath Walker Collection’, and was dedicated to “the Brisbane Aboriginal and Islander Council whose policy is self-determination”.The second edition, published in 1981, was dedicated to “the many people, both black and white, who are fighting for a Makarrata (Aboriginal Land Treaty)”. The third edition, entitled, ‘My People’, was published in 1990 and was the first book to bear the name, Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

The History Council of NSW would like to thank the Jessie Street National Women’s Library for their enthusiastic involvement in History Week 2016, and for sharing these amazing stories of neighbours and women alike.

All images courtesy Jessie Street National Women’s Library.